Article © Eric Thomas, uploaded October 14, 2018.

This article reviews the pros and cons of building a breeding group of fish using wild caught or captive bred sources. It explains some of the terminology used when discussing animal husbandry and bloodlines and demonstrates how using F1 and F2 generations as breeding stock can impact the genetic quality of your fry.

I've been keeping and breeding tropical fish since I was a child; my brother and I started keeping fish when I was about seven or eight years old. Our first spawning success was a pair of convict cichlids (no surprise), but in a few short years, we were keeping and breeding another South American cichlid (Geophagus steindachneri) and some of the newer Mbuna appearing in the hobby at the time (Melanochromis auratus, Labeotropheus fuelleborni and Metriaclima zebra), as well as one species of riverine African cichlid (Steatocranus casuarius). Back then, almost all the fish available at our LFS were wild caught fish. To my knowledge there were few fish farms operating at that time (late 1960's and early 1970's), except perhaps if you were looking for goldfish and guppies.

I took a nearly 40 year hiatus from the hobby, then returned in the early 2010's. This time, I was stuck on corys and plecos. From my childhood, catfish never seemed like fish that could be bred in captivity. But once I had my first successes (albino corys and albino bristlenose plecos, again no surprise), I was hooked and wanted to get and spawn even more exotic species.

This got me thinking: if I want to buy some new fish, in order to start a new breeding group, which is better for me to buy, wild caught (WC) fish or captive bred (CB) fish? And if I buy CB fish (sometimes also referred to as "tank raised" fish), what is the significance of buying fish labeled F1, F2, or F3? What are the implications for my future husbandry success and the health of my fry if I start with F1, F2, or F3 parent stock?

As to the first question, this has been addressed many times in the past and can be summarized simply: For WC fish:

- POSITIVE: WC fish provide the benefit that the specimens you buy will probably not be very closely related to each other, therefore offering you more diverse genetic stock; this is a strong "plus" when considering the health of fry.

- POSITIVE: Since they are wild, you can be confident that the body characters and color patterns they possess are representative of the natural species, as opposed to some manipulated shape or color morph created by humans using selective breeding.

- NEGATIVE: WC fish run the highest risk of being infected with any number of parasites or pathogens (both familiar and exotic), and their health history is completely unknown, so you have big negative wild cards there.

- NEGATIVE: WC fish may require more attention and effort from the fish keeper to help them adapt to captive conditions (e.g., water quality, foods offered, water change routines) and may be more likely to die without the extra care.

- NEGATIVE: For some species, wild populations are under strong environmental pressures for survival (primarily habitat loss and degradation and in rarer cases also over exploitation). Purchasing WC fish creates the demand for additional collecting, thus further stressing wild populations. (On the other hand, there are also positives to this in terms of preserving local populations tied to the economies where the fish are collected).

- NEGATIVE: WC fish are often misidentified by exporters, importers and retailers, meaning you may not get the fish you want. That said, many hobbyists regard this as a POSITIVE because it also means many WC imports will contain "contaminants" of other species mixed together, and the hobbyist can search for unusual or rare species among the more mundane imports.

For CB fish:

- POSITIVE: CB fish, if obtained by well managed breeding colonies, come from parents that are well cared for, and thus the offspring you buy are less likely to be disease or parasite-infected (at least with respect to more exotic pathogens; Ich and other common aquarium diseases are still be a concern). Unfortunately, this benefit can easily be lost because CB fish are typically mixed with WC fish during the wholesaling and importing process, exposing CB fish to many other diseases.

- POSITIVE: CB fish are often also less expensive to buy than WC fish, because you don't have to pay for as many middlemen in the supply chain; also, if the fish are healthy, then sellers don't incur as much incidental loss along the path from breeder to retailer, and this helps keeps the price down. This is also more planet-friendly as fewer airmiles may be required to deliver fish to stores.

- POSITIVE: CB fish are usually much better adapted to the types of water conditions found in home aquaria, and readily take prepared foods. This is not universally true, but would be species-specific.

- POSITIVE: One more positive is that by purchasing CB fish, you are reducing the demand for the harvesting of wild fish in their native habitats, which may help their natural populations (but this is debatable, and I won't get into it here).

- POSITIVE: CB fish are more likely to be positively identified (except see below about the potential for interspecific hybrids).

- NEGATIVE: When buying CB fish, especially if you are buying a group of fish from a single source, you must consider the matter of genetic diversity within your group and the possibility that the fish you buy are inbred.

- NEGATIVE: This raises the possibility that your genetically homogenous fish may not have bodies/colours representative of wild fish, and

- NEGATIVE: It raises the risk of genetic defects in future generations, if your fish spawn.

- NEGATIVE: When not properly managed, breeder stock at large commercial fish farms can be contaminated with multiple species of fish; as a result, the farms may be selling interspecific hybrids under the names of well-known species.

In an ideal world, we can always buy genetically diverse fish from captive-bred sources. If you think about it, this is the goal of zoos and related programs that work collaboratively to captive - breed endangered species. The genetic heritage of CB offspring is tracked in these programmes so that when the offspring grow up, they can be matched with and mated to other individuals from diverse genetic backgrounds.

If maintaining genetic diversity in offspring is the goal of professional breeding programs, how does it relate to us as fish keepers/breeders? How do we interpret technical terms related to the genealogies of CB fish, to ensure that we can assemble breeding groups of genetically diverse fish? And how do we "manage" our own spawns to ensure that we don't lose that genetic diversity from spawn to spawn? What we are interested in requires that we be aware of the lineages and genealogies of the fish we want to buy and to breed.

Let's start by defining some terms and then I'll offer some perspective. Genetically, scientists and genealogists use terms like F1, F2, F3, etc., to refer to generations of offspring. Most fish buyers don't mind buying F1 fish but become increasingly concerned as the F number increases. But what do F numbers mean? What do they tell us about the genetics of the fish we are buying? And why are F1 fry safe to buy, but F2 and on are not as highly desired?

The "F" in F1, F2, etc., is an abbreviation for the word "filial", which means the offspring (either son or daughter) of a particular set of parents. Of importance to us, this means that all fish referred to as "filial" with the same number are therefore related to each other as siblings, having the same parents.

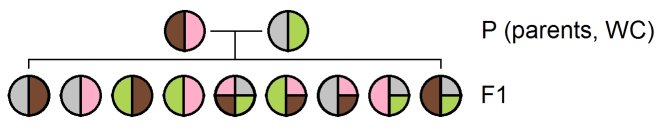

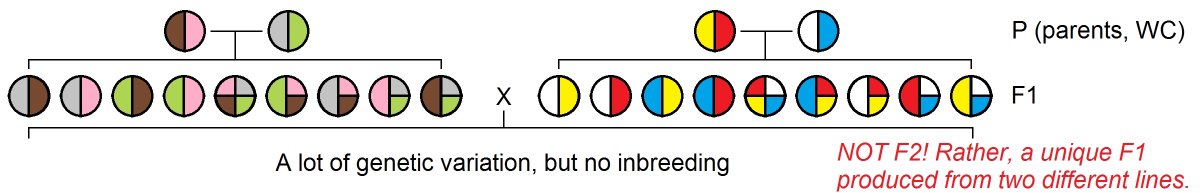

Imagine buying two WC fish of the same species. As stated before, these fish are (presumably) unrelated to each other (or as much so as we can expect from any two random individuals in a population). If the WC fish breed, then their offspring (the first generation of offspring (F1) of these parents) are a genetically unique mixture of their two unrelated parents (Figure 1).

Figure 1. First filial (F1) offspring of two unrelated WC parents. Parents are portrayed with two colors to represent the genetic contributions of their own respective parents (i.e., the grandparents of the F1 generation).

Figure 1. First filial (F1) offspring of two unrelated WC parents. Parents are portrayed with two colors to represent the genetic contributions of their own respective parents (i.e., the grandparents of the F1 generation).

Figure 1 is an oversimplification of the genetic variation that will be produced from these two parents. Before explaining further, let me be clear that I illustrated the parents and offspring without indicating gender (usually males and females are depicted with squares and circles, respectively); I am using circles to represent both sexes throughout all these charts.

Critical to the illustration is the fact that no matter which F1 individual you examine, their genetics (colors) are half from one parent and half from the other, increasing the probability that the fry have mixed alleles for genes (heterozygosity). If the same parents breed again in the future, the new offspring are also F1, since they have the same parents. This will be true for as many spawns as the original parents produce, no matter how much time elapses (Figure 2).

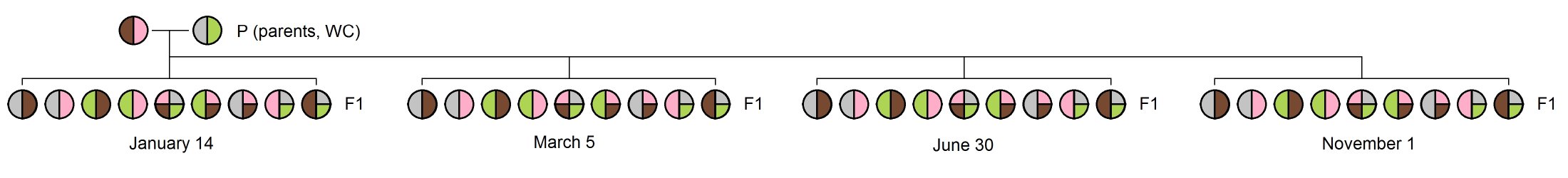

Figure 2. First filial (F1) offspring of two unrelated WC parents, resulting from four different spawns over time. Although the four spawns occurred on separate dates, all fry are considered F1 with respect to one-another because they share the same parents. Color coding as in Figure 1.

Figure 2. First filial (F1) offspring of two unrelated WC parents, resulting from four different spawns over time. Although the four spawns occurred on separate dates, all fry are considered F1 with respect to one-another because they share the same parents. Color coding as in Figure 1.

Conclusion 1: All F1 offspring from WC parents are (genetically speaking) just as representative of the species as would be any random WC individual and have as good a probability of being heterozygous as any WC fish. (Disclaimer: I am NOT saying the population of F1 offspring obtained have the full range of genetic variation found in a wild population; I am saying that any F1 individual I obtain could have been found in the population by random capture, just as the WC parents I began with were also random samples from the same natural population).

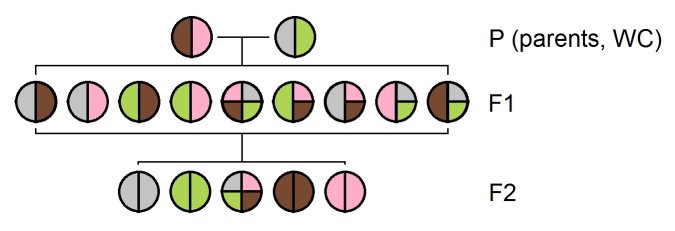

If two of these F1 offspring spawn together, regardless of whether they are from the same clutch, or from two different spawns by the same parents, then the resulting offspring are now called F2 offspring (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The range of possible second filial (F2) offspring possible from the range of F1 parents represented. The F2 offspring are simply depicted to portray the four possible extremely unlikely outcomes (pure forms representing the contributions of the four grandparents) and a single mixed individual intended to portray all possible other combinations (infinite) of F2 fry possible.

Figure 3. The range of possible second filial (F2) offspring possible from the range of F1 parents represented. The F2 offspring are simply depicted to portray the four possible extremely unlikely outcomes (pure forms representing the contributions of the four grandparents) and a single mixed individual intended to portray all possible other combinations (infinite) of F2 fry possible.

We now see the first signs of "inbreeding:" As shown in the F2 offspring, theoretically some individuals could be ending up with genes of the same kind; in other words, the F2 generation represents the first generation where potentially bad or good alleles (gene variants) begin to get recombined and homogenized (homozygosity) in the new babies.

Conclusion 2: All F2 offspring from F1 parents are (genetically speaking) now at risk of becoming homozygous for any of the genes they carry. This increases the possibility that harmful traits or shape/color-modifying characters might be expressed.

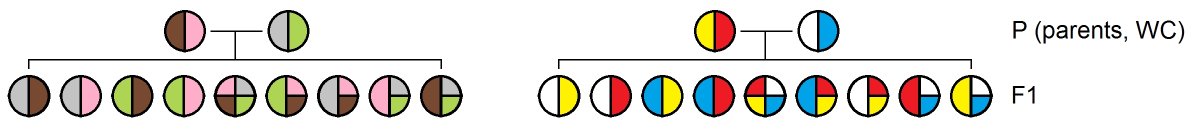

If two F2 siblings spawn together, their offspring are now called F3 offspring. With each passing generation of offspring mating with their own siblings, we repeatedly reshuffle the same set of genes, with some genes left out of the resultant fry (offspring get only half of each parent's genes) and little chance of introducing new genes (by mutation, which is a relatively rare event). As a result, the offspring of later generations (F3, F4, etc.) have less and less genetic variation, thus increasing the risk for expression of genetic diseases. However, captive breeding doesn't have to create such deleterious effects. Imagine two different pairs of WC parents. Each pair spawns (a different female with each of two males), creating two clutches of offspring, each F1 to their own parents (Figure 4).

Figure 4. First filial (F1) offspring produced by two unrelated pairs of WC parents. As before, parents are portrayed with two colors to represent the genetic contributions of their own respective parents (i.e., the grandparents of the respective F1 spawns).

Figure 4. First filial (F1) offspring produced by two unrelated pairs of WC parents. As before, parents are portrayed with two colors to represent the genetic contributions of their own respective parents (i.e., the grandparents of the respective F1 spawns).

This time, because the parents are not likely related to each other, these two different F1 generations are NOT F1 to each other. That means you can cross-breed F1 fish from one set of parents with F1 fish from the other set of parents, and the resultant fry are NOT F2 offspring (Figure 5). The new offspring are, in principle, just as genetically diverse as any WC fish you could buy in your favorite LFS tomorrow. And there's the key to preventing inbreeding.

Figure 5. Cross breeding of two unrelated F1 lineages to produce genetically novel offspring.

Figure 5. Cross breeding of two unrelated F1 lineages to produce genetically novel offspring.

Conclusion 3: Cross-breeding unrelated F1 offspring (from unrelated parents) produces a new generation of fry which can be called F1, and which are (genetically speaking) just as representative of the species as would be any random WC individual and have as good a probability of being heterozygous as any WC fish.

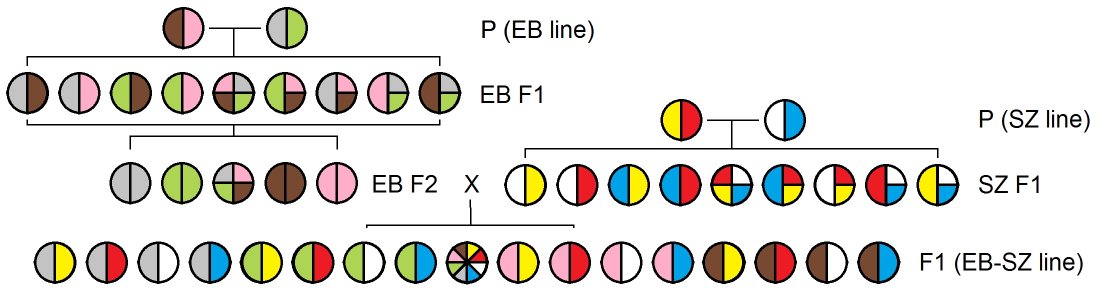

To do this right, it is important for hobbyists to learn as much as they possibly can about the source and genetic heritage of the CB fish they buy. For example, I had the great pleasure to obtain a dozen young Ancistrus claro from another PlanetCatfish member. My young A. claro are the F2 offspring of F1 fish purchased from Eric Bodrock, who obtained WC fish from Aquatic Clarity to start the lineage. Since my fish are already F2 in the Eric Bodrock lineage (I'll call this EB), I don't want them breeding with each other. So I've found another hobbyist who purchased WC A. claro from two separate retail sources (WetSpot Tropical Fish and Tangled Up in Cichlids; I'll call his line SZ). I'm going to buy an equal number of F1 SZ A. claro and let these fish grow up. When their genders are clear, I will put my F2 EB males with the F1 SZ females into one tank, and vice versa (F2 EB females with the F1 SZ males) in a second tank. This will ensure that all spawns produced (regardless of which tank they come from) will yield groups of offspring that are essentially a novel combination of F1 EB-SZ fish, not F2, not F3 (Figure 6).

Figure 5. The range of possible first filial (F1) offspring possible from the cross-breeding of EB F2 and SZ F1 parents. The EB-SZ F1 offspring are simply depicted to portray the sixteen possible extremely unlikely outcomes (pure forms representing the contributions of the eight original wild grandparents) and a single mixed individual intended to portray all possible other combinations (infinite) of EB-SZ F1 fry possible.

Figure 5. The range of possible first filial (F1) offspring possible from the cross-breeding of EB F2 and SZ F1 parents. The EB-SZ F1 offspring are simply depicted to portray the sixteen possible extremely unlikely outcomes (pure forms representing the contributions of the eight original wild grandparents) and a single mixed individual intended to portray all possible other combinations (infinite) of EB-SZ F1 fry possible.

Who knows how long into the future we'll be able to get WC fish? With habitat loss, climate change, and (hopefully) meaningful governmental/scientific efforts to protect wild populations, it seems clear that there will come a time when WC fish will be difficult or impossible to obtain. The burden is on us, as responsible caring hobbyists, to ensure that the fish we breed are managed in a careful and judicious manner to preserve the genetic quality of the fish we so love.

Back to Shane's World index.